The Florida Project

A month ago, I lamented about this year’s best picture Oscar nominees and listed the few movies I saw in 2017 that I thought deserved recognition, only one of which made the Oscar cut: Get Out. I’d like to add one more movie released in 2017 that should have been recognized for more than just a best supporting actor nomination for Willem Dafoe: The Florida Project, a low-budget film released last fall to rave reviews, though if you blinked, you might have missed its theatrical release.

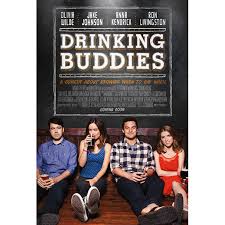

The Florida Project is one of those rare films that I gravitate toward – short on plot, long on characters and realistic slices of life. It brings to mind some other films like Beginners, Nebraska, Lovely and Amazing, The Squid and the Whale, Boyhood and the Joe Swanberg films (Drinking Buddies, Digging for Fire, All the Light in the Sky, and the like), though its portrayal of the American poor through children’s eyes has almost nothing in common with those films. In that sense, it’s like no other film I’ve seen.

Director Sean Baker’s portrait of poor families living in a rundown motel outside of Disney World is captivating, largely due to the amazing talents of child actors Brooklynn Prince, Christopher Rivera, Aiden Malik and Valeria Cotto. Much of the film is shown through their perspective, as they stroll from motel to ice cream stand to waffle house to cow pasture to abandoned homes. I marveled at some of the dialogue between the children and am curious about how much was scripted and how much was simply kids being kids, as they express wonderment of a fallen tree that’s kept growing or take delight in sharing an ice cream cone.

The adults are worthy of note too, and not just the incomparable Willem Dafoe – wonderful as the motel manager who, without sentiment, protects the lives of his poor tenants in ways large and small, a more important figure in their lives than the mobile food pantry volunteers who hand out bread in the motel parking lot. Bria Vinaite, who plays mom to Prince’s Halley, is also a standout as an aimless adult doing whatever she needs to do to pay next week’s rent, including using her daughter to hawk wholesale perfume in a country club parking lot. Yes, she’s a neglectful parent, but I found her also to be sympathetic, as her love for Halley shines through at times, though not always in the most conventional way.

The film shows a side of life that we don’t often get to see – the American poor, eking out a living, relying on each other for basic niceties, not having the luxury of caring about politics or the environment or the economy. Surviving is all they have time for. Like my experience watching the film Boyhood, I kept waiting for the Hollywood dramatic turn: a car crash, a molestation or a murder. There were times when the kids were running through a parking lot or crossing a street, and I winced, expecting one of the children to land on the hood of a car. But like Boyhood, The Florida Project doesn’t take the easy way out. Many lives are crushingly difficult, not because of life-altering events, but because of the harsh, daily grind, when one day bleeds into the next, never exercising the difficulties of the day preceding it.

Often, I value a movie on how much I’d like to see it again, and I was taken with something Richard Roeper of the Chicago Sun Times wrote about the movie. He was more harsh in his assessment of the characters the film portrays, but he still loved the film. He writes: ”…you’ll most likely not want to see (it) twice, but seeing it once is an experience you’ll not soon forget.”

I think he and I agree on this point. I’m not sure I’ll be eager to rent this movie again, even for all it’s attributes. But if you haven’t seen it once, you’re missing out.