The Phrase "Spoiler Alert."

The invention of the phrase “spoiler alert” has got to be one Man’s greatest linguistic contributions over the last decade or so. Philip B. Corbet of The New York Times has rightly pointed out how overused the phrase has become, and how it’s often used incorrectly, but for my money, overuse is preferable to the alternative.

I think of the woman who came to my home in 2002, and who – after eating our food – thanked us by divulging the ending of the movie, The Others.

I will do for you what she didn’t do for me.

!!!!SPOILER ALERT!!!!

She opened up that pouty little mouth of hers and spewed out, “I couldn’t believe it when I learned her children were dead.”

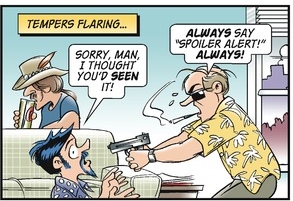

She is very, very lucky that I didn’t resort to the following (or worse):

After her egregious case of vomit of the mouth, it didn’t matter to me if she was smart or pretty, if she’d overcome obstacles in her life or helped the needy. I couldn’t possibly care less if she gave twenty percent of her earnings to charity or if she was raising three perfect little angels. None of that shit mattered to me. What mattered is she opened her mouth and ruined the ending of a movie I was excited to see. Yeah, the film had already left theaters and moved into video stores, but to me, there is no statute of limitations when it comes to revealing secrets about a piece of art.

I still haven’t told my kids about the ending of Psycho. I’ll never divulge the meaning of Rosebud, whether or not Thorwald really murders his wife, and where the quarter of a million dollars is hidden in the movie Charade. That’s for them to discover. And I sure as heck won’t mention a word about The Sixth Sense. Sure, I could try to ease my kids’ anxiety and mention !!!SPOILER ALERT!!! that the ghosts are actually trying to help, that they’re good guys (never mind the movie’s Big Secret). I resorted to this tactic when my kids were younger watching E.T. for the first time. !!!SPOILER ALERT!!! “The bad guys are actually good guys,” I said, attempting to alleviate their trepidation, but I’ll never do this again. It kills the journey.

Some people just don’t get it, including – unfortunately – much of my family. Last summer my sister-in-law blurted out the secret behind the musical, Next to Normal, the same day my daughter was to see it. And just last month, my mother, in response to an email of mine indicating that I wanted to see the movie Enough Said, wrote the following email !!!SPOILER ALERT!!!:

I fell in love with the Soprano guy, what an appealing person. Was Julia's character vulnerable, screwed up, or just terribly unkind?

Yep. So now I know the ending of that movie, too. Thanks, Mom.

I think when it comes to discussing books, films and theater, we could look to my sister for guidance. Her advice for living in a world in which the excretion of opinions is as commonplace as breathing is this:

Shut your trap.