The Great Divide by Heinz and Wrobel is complete! To stream or purchase this ten-song album, check out the following locations:

The album will be added to several other streaming sites shortly.

Heinz & Wrobel are:

Julian Wrobel – Bass

Sam Heinz – Drums

Paul Heinz- Keys and Vocals

Tracking by Brad Showalter at Kiwi Studios, Batavia, Illinois

Overdubs engineered by Paul Heinz

Orchestration on “Cold” and “End Game” by Jim Gaynor

Mixed by Paul Heinz with the help of Julian, Sam and Anthony Calderisi

Mastering by Collin Jordan of The Boiler Room, Chicago, Illinois

All songs written by Paul Heinz, except “The Unexamined Road,” music by Sam Heinz and Paul Heinz, lyrics by Paul Heinz

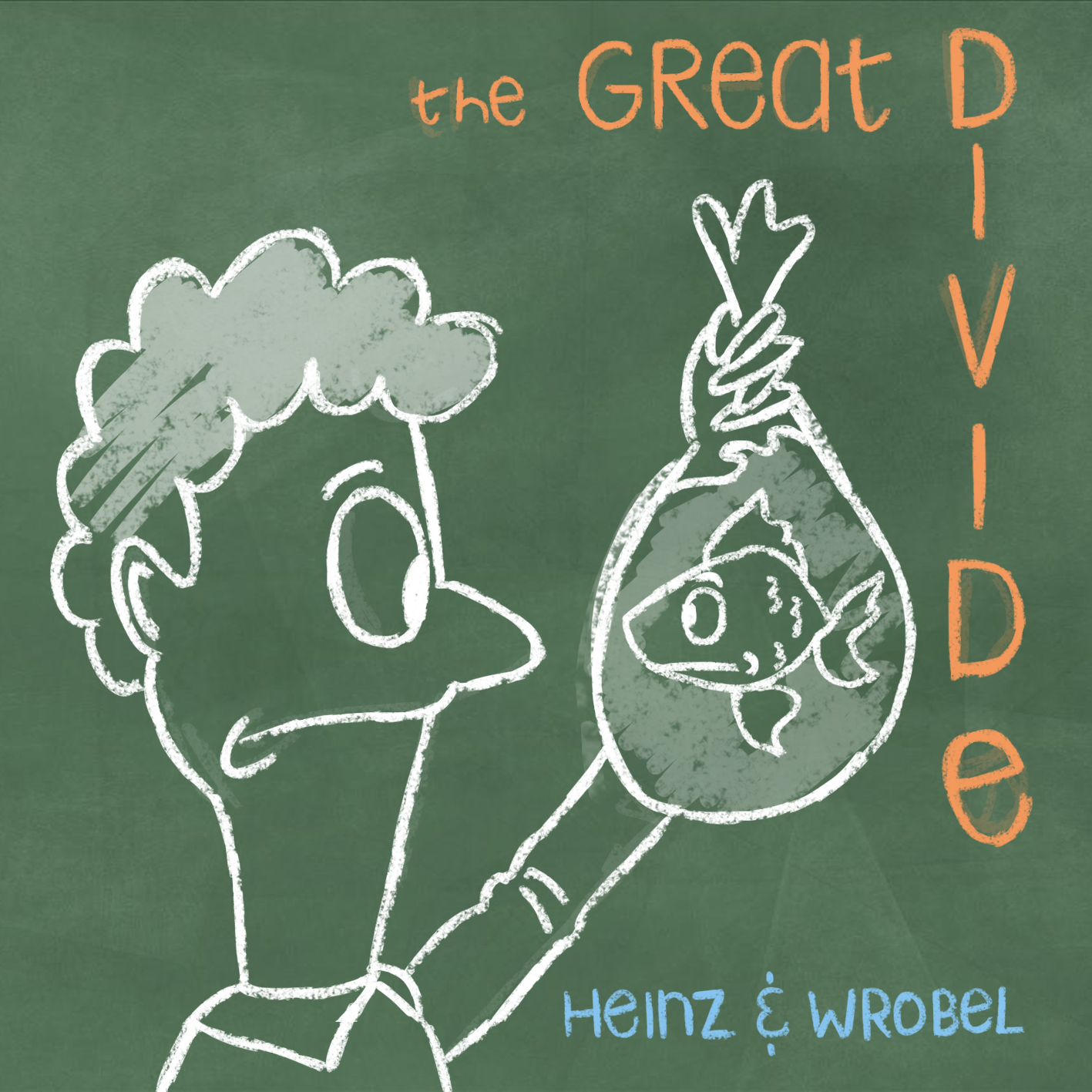

Cover art by Sarah Heinz, based on a concept by Sam Heinz

Photograph by Sam Heinz

We’d like to thank Brad for his easy-going nature and diligence, Collin for his expertise Anthony for his objective listening skills, and Jim for giving two songs the lift they required. We think “End Game” is the best song on the album thanks to you.

********************************************************************

After completing The Palisades in August of 2016 I wrote the following on my website: “I’m toying with the idea of doing my next project in about two days – all in the studio with a live band. A guy can dream, can’t he?”

Well, The Great Divide didn’t exactly take two days, but it was a hell of a lot faster this time around, for which I’m grateful.

In Spring of 2017, I began to ponder the next project, and Sam and I decided that we should record together in the studio and pound out the entire album in a day or two. The issue was I didn’t really have any songs – only half-written melodies or a refrain or a verse that didn’t go anywhere. It wasn’t until the summer when Sam was at camp for seven weeks that I began to diligently evaluate which half-written pieces of music were worth pursuing and which should be scrapped. It took a while.

That summer, I initially decided to create a thematic album called “Confessions and Confrontations,” with several instrumental interludes and a few musical themes that would repeat throughout the album, a pretty bold idea for someone who didn’t really even have any songs completed. I worked hard on songs called “Eat Crow,” “Shouldn’t I Get Some Credit,” “Stretched Too Thin,” “I Once Fell in Love with a Girl,” “The Line,” and “Something Lost.” Alas, none of these made the cut.

Instead, a few other songs with working titles of “What Are You Going to Do” and “I Don’t Want to Talk About It Now” began to take shape, along with some very old ideas, such as one called “Same Old Shit,” which originated in the summer of 2013. I also resurrected two song that I had, in fact, completed: one called “Cold,” which I’d written in 2001 and even recorded a demo of in maybe 2006; and “Put You Away,” composed sometime around 2009, but it never felt right with previous projects. This time, it fit perfectly with the minimal instrumentation we were providing.

One of the pieces I worked on in July of 2017 was a little chord intro that Sam had composed prior to leaving for Wisconsin. This eventually evolved into a rather intricate little ditty called “The Unexamined Road,” a song that was known as “Untitled” up until November because I wasn’t happy with the lyrics. Eventually this song sounded so darn good that it became the album’s opener.

I wrote most of the music for what became “Lies of the Damned” in April of 2006, but there it sat until 2017. I needed an idea to help drive what I knew was an angry song. Eventually, I came up with a sketch of a type of person I’ve met over the years: an odd combination of extreme self-centeredness, yet monstrously insecure. I’ve known three or four people who fit this mold to a “t,” and once I knew the object of my angst, I was able to pound out the song very quickly!

“What is True” developed from a tune that came to me in a dream in December of 2016. I was meeting my friend Scott Baldwin at an outdoor bar tended by none other than Rufus Wainwright, who was suffering badly of a cold. He said that recently the “juices were flowing,” meaning he was composing a lot lately. I asked him to fix me a sandwich, and he began singing his latest creation, “You say, I don’t want to talk about it now…” I woke up and wrote it down and eventually developed it into a tale inspired by a friend of mine. Similar to “I Can’t Take You Back” from Warts and All, it’s the heartbreaker on the album.

“Are You Gonna Fight For Her,” was nothing more than a verse and unfinished chorus in April of 2016, but in the summer I managed to write the bridge and instrumental sections that really made the song work. I was the least confident that this song would work on the album, but once drums and bass were added, it all came together beautifully.

“Your Mother’s House” started once again with just a verse in May of 2014, and in April of 2015, as I was trying to write a chorus for the song “The Palisades,” I came up with a chord progression that eventually fit perfectly as the second half of the chorus for the former. But I still had to write the first half of the chorus, which I finally completed at the end of August, along with the middle bridge.

I wrote the first several verses of “End Game” in September of 2016, just after completing The Palisades, but I didn’t finish this tune until over a year later, when I composed the build-up leading to the end of the song. The “bombastic” section of the tune came in July, written originally as an instrumental theme to insert between songs, but then I recognized it would fit in the actual tune with a lyric. How this all came together is a bit miraculous, and I’m grateful that it came off as well as it did. By October I had to come up with a title, and “End Game” came to me in a flash.

Little by little, songs were completed, while others were discarded. Sometime in the summer, Sam asked if Julian would be up for recording with us, and he was excited to join the project. On August 21 I drove Sam and Julian and a friend of theirs to Missouri to watch the total eclipse, and along the way I mentioned the name of the upcoming album and the concept. They were both rather unenamored with the idea of “Confessions and Confrontations,” so I took this under advisement until I finished the song “Diverge,” a tune I’d written the first verse for back in 2012 but didn’t complete until October of 2017, the last tune written for the album. I was so happy with this song that I was certain it would lead it off and that it should spawn the title for the album. Eventually, “Diverge” gave way to “The Unexamined Road” as the opening track, a song which remained untitled and which I struggled mightily to come up with a different refrain, but none fit as well (An Energizing Trail? A Uninspired Path?) This is one of those instances where the lyrics don’t quite reach the same level as the music.

I liked the idea of The Great Divide as a concept and considered viewing the new album as a collection of songs about conflict. I remember that the band Big Country had a song with this title off their Steeltown album, and after scouring through the lyrics of this song I came up with a list of possible titles for the album: “Sighs and Youth,” “Fire Away,” and “The Token Door.” Eventually I thought, “Screw it. Just call it The Great Divide.” So there you are.

Once we knew the title of the album, Sam came to me with a concept for an album cover and I shared it with my daughter Sarah on January 8th at 3:38PM. I wrote: “The drawing would be in the simplistic style of The Far Side comics and the Duke album by Genesis, and it would be a close-up of a inexpressive guy holding a baggy at eye level filled with water and containing a gold fish, and the gold fish staring back at him. Hence, ‘the Great Divide.’ Get it?” At 4:29PM she sent me the cover of the album. Tell me she wasn’t looking for a reason to procrastinate finding an internship! Sam and I looked at the cover after his drum lesson and immediately fell in love with it.

On October 26, I met with Sam and Julian and went through the whole album and how I wanted to approach things. We discussed recording in February or March and decided not to record vocals at that time; it would be difficult enough to get the instrumental parts down. We began rehearsing in November, and I was amazed at the parts that Sam and Julian created, producing a much better product than I ever could have managed on my own, and because we had so much time to rehearse, it ended up sounding better than if I had outsourced things to professionals. Sam and Julian created “parts” for the songs; they didn’t just play along to a chord chart.

On February 17 we spent thirteen hours at Kiwi Studios in Batavia, Illinois, where I had recorded basic tracks for The Palisades, and finished piano, bass and drums for all ten songs. Pretty impressive. Brad Showalter engineered this time, and he was laid back, unhurried and flexible, making the whole experience very enjoyable. Once again, Sam and Julian played like pros, punching in seamlessly, playing to click tracks for some songs and others on the fly. The most difficult tune to record by far was “Lies of the Damned.” By some minor miracle, “End Game,” which we recorded without a click track, we achieved on just the second take. It is our favorite on the album.

I recorded vocals over the next few weeks into March, and then added a few backup vocals, percussion and synthetic strings, but what I really wanted was for composer Jim Gaynor to record orchestration for “Cold” and “End Game.” In late March he was ready to add some tracks, and the results are superb.

After several grueling rounds of mixing (an art form I still struggle with mightily on every album), I finished things up and set a date to master the product at The Boiler Room in Chicago, where Collin Jordan put the finishing touches on the album. It helped that we had set an album-release concert for May 5th, which required me to wrap up the album quickly, whereas I’d normally spend another few months mixing everything to perfection (but never achieving it).

We sent things off to Diskmakers and made physical CDs for the first time since my album in 2003, The Dragon Breathes on Bleecker Street.

All in all, a very satisfying and enjoyable project, made all the more meaningful by having my son and his friend, along with my artist daughter, involved. And my vocalist daughter is able to join us on stage for the record release concert, so all three of my kids were involved in some meaningful way. Now, if I could only get my wife involved somehow on the next project!

Join us on May 5th at 7PM, as Heinz & Wrobel host a record release party to celebrate the completion of our new album. Email me for details.