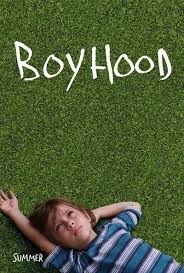

The Movie Boyhood: See it

The monumental achievement of Richard Linklater’s latest movie, Boyhood – in which he follows the fictional lives of a family for a dozen years – might be easy to overlook without first comparing to other art forms to put things into perspective. Imagine asking a musical artist to record one song in one month out of the year for twelve years with the intention of making a seamless 12-song album. The Beatles couldn’t have done it. Led Zeppelin would have failed at this endeavor. Michael Jackson? Forget about it. What about asking an author to write a chapter in one month out of the year for 12 years to create a tight, page-turning novel? A near impossible endeavor.

Artists evolve. Their interests change. Their skills change. Technology changes. Artists immerse themselves in a project often at times to the detriment of everything else going on in their lives, and if they’re lucky, their myopic pursuits result in a near-perfect piece of art. That Linklater was able to achieve the latter despite taking twelve years to do it is nothing short of remarkable.

In Boyhood, starring Ellar Coltrane, Lorelei Linklater, Patricia Arquette and Ethan Hawke, twelve years pass before our eyes, as the characters evolve and age in mostly very ordinary ways. Richard Linklater began filming in 2002 and wrapped up finally in 2013, all the while directing a number of other movies, including the second and third installments of the “Before” trilogy, which – like Boyhood – are also a study of time and the ordinariness of life.

As the film progressed, I – far too accustomed to the typical movie experience – waited for tragedy to strike: a rape, a car crash, a stupid drunken accident. And though the movie isn’t absent drama, it does illuminate what I wrote about just a week ago: that normal everyday lives are interesting in and of themselves. Linklater sets up a few scenes where something awful could have occurred, only to proceed without fanfare. I believe this was done on purpose, as it shows just how tenuous our lives are, as we take risk after risk after risk on a daily basis, only to find that most of the time, we escape unharmed. We manage to survive in spite of our carelessness.

At two hours and 45 minutes, the movie for me was about twenty minutes too long, and Arquette’s character’s inability to recognize a man’s shortcomings grew tiresome, but those are minor quibbles. More important was an observation my daughter made about the main character, Mason, played by Ellar Coltrane. She said that Mason was a walking cliché for the emo subculture, whereby every cynical, morose viewpoint is spouted as unique and interesting in spite of it being taken straight out of the emo handbook. Here’s a summary from http://uncyclopedia.wikia.com/wiki/Emo

Emo is a type of subculture…loosely rooted around punk rock with its own distinct style of music, fashion, argot and other trappings in a desperate, though ultimately hopeless attempt to pronounce their uniqueness. As a rule of thumb, a person described as "emo" will often be from a comfortable, middle-class background with liberal parents. All of this is irrelevant to an emo who will consider themselves misunderstood and repressed regardless of reality…They all suffer from severe narcissism, leading them to believe that they alone know what pain is, and that no one understands them…on the plus side, emos have made great strides in the fields of photography.

Well, damn. My daughter was spot-on! The character of Mason is in fact a walking cliché. But guess what? So are a lot of the people we meet every day. Sure, I think it would have been more exciting if Mason had been an outgoing guy who was into sports or drama or music, but Linklater needed to let the film evolve as the actors evolved, and my guess is that the fictional Mason wasn’t too far removed from the real-life Coltrane since the script was written over the 12 year-period and very much tailored to the actors involved.

That this film came to fruition is a minor miracle. So many things could have gone wrong: actors could have died or decided they didn’t want to finish the project. A major life event in any of the actors’ lives could have put the project on hold. What would have happened had it turned out that the girl or boy couldn’t act? Somehow Linklater keeps it all together, and manages to allow time to elapse before our eyes without editing flourishes; sometimes a new scene begins and only upon seeing an older Mason do we realize that a year has passed. Linklater similarly avoids sentimentality (except for one completely unnecessary scene in a restaurant). I imagine that in the hands of another filmmaker, Boyhood would have succumbed to the token flashback near the film’s end, whereby Arquette recalls the early lives of the children she’s sending off into adulthood. Yes, I would have bought this type of flashback hook, line and sinker – I love that kind of crap – but I give Linklater credit for refusing the low-hanging fruit.

See the movie.